By Thomas Hübl

For the past eight years, I’ve worked closely with an experienced emergency room doctor. Every day, he witnesses acute human pain and suffering, over and over. Often, he has to make life-or-death decisions in the space of minutes, or even just seconds. Objectively, his job is incredibly stressful. That stress never overwhelms him, though, because he and his colleagues have learned how to confront, channel, and process their intense experiences. They are strong and resilient.

But as COVID-19 began to hit his hospital, he noticed that this crisis felt different. He couldn’t stop the stress flooding his emergency room from wearing at him anymore. Just a month into the pandemic, he told me that he felt more burned out than ever. In fact, he was completely depleted.

He’s not the only strong person who’s struggled with the pandemic. Indeed, many of us recognize, on some level, that the stress of COVID-19 seems to have taken a special toll, unlike the strain we’ve felt when facing other tragedies in our lives. That’s because, although we often focus on the ways the pandemic has affected us as individuals, COVID-19 is a collective trauma, a uniquely destabilizing force with not only the power to overload even the most robust psyches and support systems, but also the potential to subtly embed stress and pain within the very veins of society for generations to come. Daunting and distinct as this type of stress may seem, however, we can still effectively confront, channel, and process it—with the right mix of approaches, support, and understanding.

He’s not the only strong person who’s struggled with the pandemic. Indeed, many of us recognize, on some level, that the stress of COVID-19 seems to have taken a special toll, unlike the strain we’ve felt when facing other tragedies in our lives. That’s because, although we often focus on the ways the pandemic has affected us as individuals, COVID-19 is a collective trauma, a uniquely destabilizing force with not only the power to overload even the most robust psyches and support systems, but also the potential to subtly embed stress and pain within the very veins of society for generations to come. Daunting and distinct as this type of stress may seem, however, we can still effectively confront, channel, and process it—with the right mix of approaches, support, and understanding.

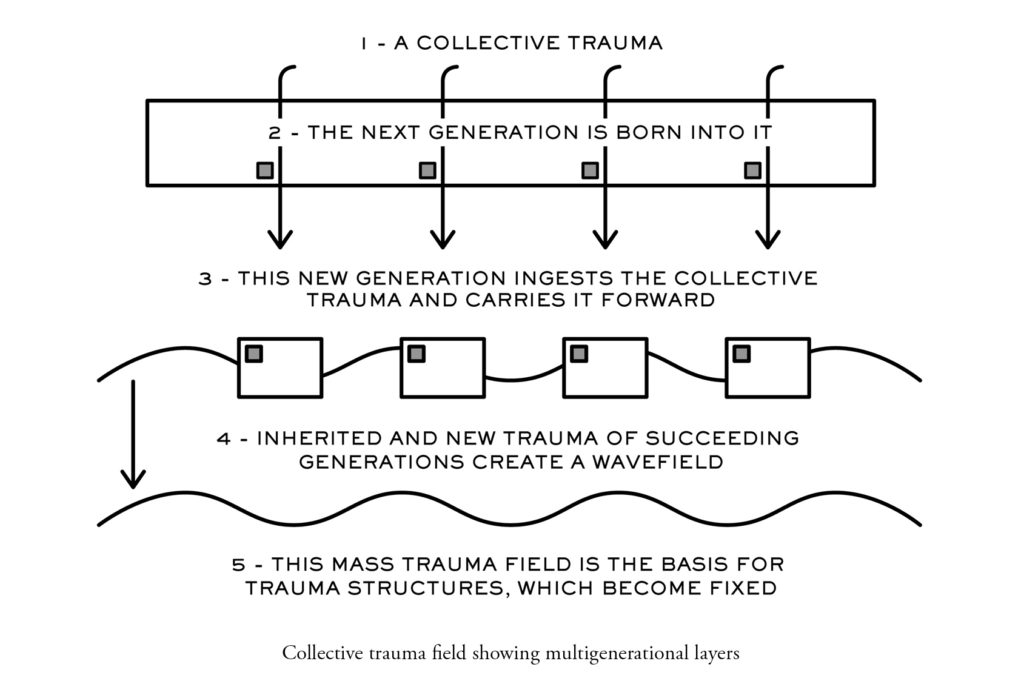

Collective trauma occurs when a sudden shock upends not just one person’s life, but the lives of everyone in a community. This shock will not touch everyone equally, as trauma almost always strikes the most marginalized members of society hardest. But if it imparts enough force to cause a substantial portion of a group to struggle all at once, and strikes in such a way that it damages or breaks the institutions people used to connect with and support each other, then the affected society will rapidly fragment, leaving every individual increasingly isolated with their pain. And these shocks rarely pass through a social system quickly, then dissipate. Usually, they pulse through again and again, each time deepening the wounds caused by an initial shock. Given enough time, elements of responses to this chronic and pervasive trauma—like a predisposition towards anxiety or a tendency towards psychic numbing—can get worked into a community’s very culture, or even into their genetic code, then get transmitted down to future generations.

A variety of spiritual traditions have long recognized this phenomenon. But Western mental health experts started developing the modern, scientific concept of collective trauma in the mid-20th century to describe widespread patterns of pain they observed among the descendants of communities subjected to some of humanity’s greatest atrocities—like the Native American genocide, the Holocaust, the American chattel slavery system—and their ongoing reverberations.

The COVID crisis may not seem equal to these injustices. But when entire cities shut down in attempts to contain the disease, several mental health experts recognized the first shocks of a collective trauma. At the same time that many of us began to feel a void-like uncertainty about the risks of this unknown sickness—about who or what was safe—vital public health measures closed spaces and fractured bonds that most relied on to feel safe and connected in the world, to process stress and pain. Death counts and stories of both illness and isolation dominated not only the news, but also entertainment and everyday conversation all over the world. Increasingly, our entire lived environment came to center around the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the summer of 2021, groups like the American Psychiatric Association started to conceptualize the scale of the impact of this year of perpetual and inescapable instability, documenting marked spikes in mental health issues across the globe. However, there has been little guidance offered on how, as individuals and communities, we can manage these distinct patterns of stress and anxiety.

In the summer of 2021, groups like the American Psychiatric Association started to conceptualize the scale of the impact of this year of perpetual and inescapable instability, documenting marked spikes in mental health issues across the globe. However, there has been little guidance offered on how, as individuals and communities, we can manage these distinct patterns of stress and anxiety.

For almost two decades, I have worked with mental health experts and spiritual teachers from all over the world to develop tools and techniques to help individuals and groups acknowledge, process, and integrate collective traumas like the pandemic. The endeavor often seems daunting, given the magnitude of all the concerns and pressures we, and everyone around us, have faced during this pandemic. But confronting and channeling our stress and anxiety really starts with one simple step: We need to take a break on occasion to make sure that we can still feel ourselves.

Collective trauma overloads individuals and communities with unbuffered stresses. Just like a computer forced to process too much data too quickly will start to lag, then crash, our nervous systems gradually numb when overloaded, until we shut down. This numbness often creeps up on us so gradually that we do not even notice it. Taking minutes away from our everyday churn to focus solely on our bodies and emotions both gives us a chance to recognize how an unfolding crisis is affecting us and gives our bodies space to catch up on processing everything.

This break does not need to take the form of focused meditation. It can be a walk, a dinner, or even something productive like a series of chores—as long as the activity is slow and calm enough to give you the space to reflect on, and your mind a chance to work through your core physical and emotional feelings. But if you struggle to connect with yourself like this, either because you are unaccustomed to it or because your mind is racing, then certain skillful practices can help you to slow down and focus—like regulating your breathing, reflecting on one part of your body at a time as you exhale slowly, and seeing how much longer you can maintain that focus with each breath.

If you have reached a critical level of stress and isolation, this process of self-reflection will likely be painful. We may not recognize it, but to avoid this pain we often find any excuse to stay in motion, compounding the stress building upon our minds and bodies and exacerbating our risk of a total shutdown. In normal times, our communities may notice that we’re buzzing constantly, and help us find the time and space we need to slow down and process our stress. The fragmentation of a collective trauma often robs us of this support system. So, we need to make self-reflection into a practice—a task we hold ourselves to completing on a regular basis. And we need to acknowledge that failing to face our own pain and discomfort doesn’t just hurt us. Letting ourselves fall into total numb disengagement breaks another link in our social system, and transmits pain to others. Hopefully, this awareness is enough to help us move through a few minutes of discomfort.

If you realize that you have already gone partially or fully numb in the face of crisis, then you need to make an effort to reconnect with the wider world. This can be as simple as calling a friend; just talking to another human honestly about our numbness and how we reached it is often enough to jolt us back into feeling. If your social network has already been strained too far by pandemic stress, leaving you with few options, you can always reach out to a professional, like a therapist.

However, if self-reflection practices reveal that you are still connected to your own feelings, and if you believe that you have the bandwidth and drive to help others, then you can start rebuilding the fractured communities around you. You don’t need to join a special organization to do this. Just need to let your community—friends, neighbors, co-workers—know that you are around as a resource. That they are not as alone as the pandemic context may convince them they are.

However, if self-reflection practices reveal that you are still connected to your own feelings, and if you believe that you have the bandwidth and drive to help others, then you can start rebuilding the fractured communities around you. You don’t need to join a special organization to do this. Just need to let your community—friends, neighbors, co-workers—know that you are around as a resource. That they are not as alone as the pandemic context may convince them they are.

If you pursue this path, just remember: Do not try to become the sole savior of your community. Taking on too much is a good way to break your self-regulation and tip into harmful stress and numbing. Use your practice of self-reflection to make sure that you always maintain space for yourself. And trust that doing what you can is enough—because if we support others to the point that they are able to support their own radial communities, we will often find that our small efforts gradually cascade into a process of communal healing.

These individual steps are only one piece in a larger puzzle of healing. Beyond self-regulation and mutual support, our leaders and institutions need to give us space and safety to recognize the overall toll of this pandemic together, discuss that impact openly and honestly, and ultimately process it into collective meaning. This may take legislation and innovation to build resources and venues. It may mean confronting the reverberating effects of other, older collective traumas that have already weakened the bonds necessary for this type of work. It will certainly take time.

But putting in the hard work to confront, channel, and process the unique stress of this collective pandemic trauma is absolutely necessary, both to limit the long-term effects of this stress on our culture and to build the resiliency that will help us face new collective traumas moving forward.